Ryder Cup Preview

Pour l'amour du golf!

There’s a lot more at stake than a Ryder Cup - golf’s ultimate extravaganza is set to take the game in France to a whole new level, writes Mike Phillips

By Mike Phillips

Up on the plateau at Le Phare, the young boy peered down into the Bay of Biscay and watched as the huge waves crashed down onto the rocks. He snapped back into life as a wealthy foreigner extended a curiously shaped wooden stick in his direction; he grasped the implement and placed it carefully in his bag.

Welcome to Biarritz, in the south-westernmost corner of France, as the nineteenth century began to fade. It was a clash of cultures up here at Le Phare, just as it was in the town below, where not even the construction four decades earlier of a lavish summer palace by Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III, and the resultant influx of sun-seeking royals from across Europe, could uproot the deep working instinct of the locals.

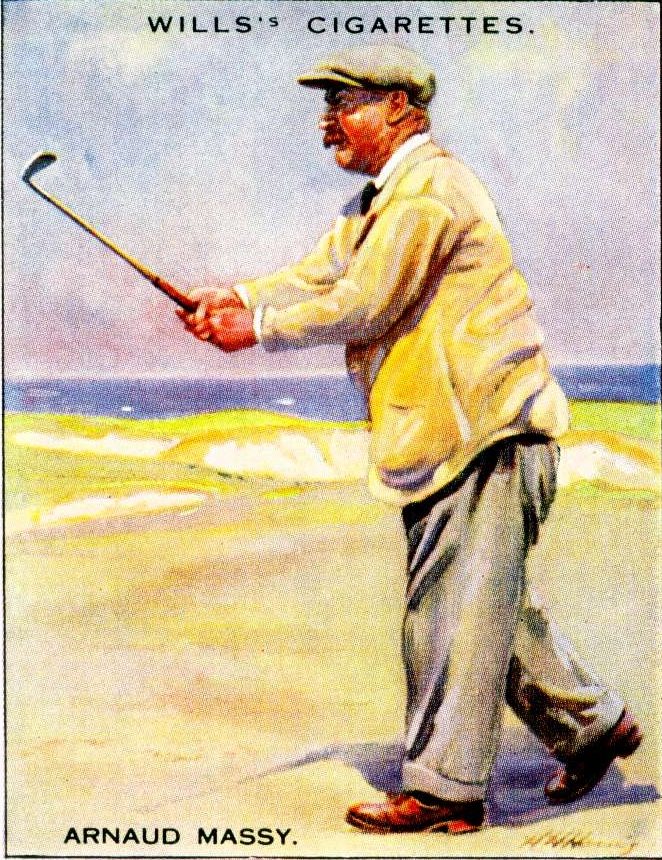

Farming and fishing, fishing and farming: they are staples of life in the Basque country, now as then. The young boy, Arnaud Massy, a sheep farmer’s son, fished for sardines and took them to the great covered market of Les Halles. For extra francs, he carried the bags of foreigners up on the plateau, handing them their wooden sticks and watching with intrigue as they struck their small rubberised projectiles high above the smooth grass.

Sadly for the foreigners – Brits, naturally – the boy was watching rather too closely, and by the age of 30 had become the first outsider to win the British Open, showing Harry Vardon, James Braid and John Henry Taylor a thing or two on the links at Hoylake. This was in 1907, fully 14 years before an American managed to win in the ancient game’s homeland.

By the time of his victory in Liverpool, Massy had already won the inaugural staging of the continent’s oldest national championship – the French Open, staged at the fabled La Boulie course outside Paris and part of the reason why top American players began to cross the Atlantic a century ago. That elegant track, still part of the exclusive Racing Club de France, staged the French Open as recently as the 1980s, when Seve and Nick Faldo walked away with the honours. Just a mile and a half from the Palace of Versailles, La Boulie crowned only kings.

Just down the road in Guyancourt, built on an unremarkable slab of common land between Versailles and the 63,000-acre park of Haute Vallée de Chevreuse, lies the modern-day hub of the sport in France, Le Golf National. Conceived as a permanent home for the till-then-nomadic French Open, the venue was designed as a magnetic centre for the national game – a Roland Garros of golf, if you will.

Co-designed by Hubert Chesneau, a former head of the French national golf federation, FFgolf, and the late Robert von Hagge, whose fairytale woodland courses at Les Bordes in the Loire Valley are slated among Europe’s finest, the facility opened in late 1990. Its first Open was claimed by Argentina’s Eduardo Romero in June the next year, by two strokes from José María Olazábal and Sam Torrance.

The signature Albatros course – measuring 7,247 yards with a par of 71 – has been the subject of a tremendous renovation, with a complete overhaul of its irrigation, tee areas, bunkering and presentation, with an eye on France’s first Ryder Cup this September. With closely matched, star-studded teams bolstered by young guns like Jon Rahm and Justin Thomas, this year’s encounter is shaping up to be another spectacular feast of golf to savour.

Accepting, as we surely must, that the 1997 staging of golf’s matchplay showpiece on the Costa del Sol was almost entirely built around one remarkable individual – Ballesteros his name – then 2018 marks the first time a home Ryder Cup has been strategically posted beyond the confines of Britain and Ireland. In short, it’s not just a big deal for France, but for Europe too.

The event will shine a protracted spotlight on the oft-praised course, known for its firm, undulating fairways, slick greens, omnipresent water hazards and uncompromising rough. A challenging closing stretch skirting the lake and a stadium design were both carefully planned; with the delights of central Paris close by, spectators are particularly well treated here.

And there will be many of them. Some 60,000 fans a day are expected on the course and a further 10,000 on site – that’s around a third more than at Gleneagles or Celtic Manor.

Le Golf National’s transition from local club course to budding global destination – and most likely an Olympic venue come Paris 2024 – has been surprisingly recent, as general manager Paul Armitage explains.

I ask him to summarise the challenge of the Albatros course from a professional players’ perspective.

'Damn hard!’ he laughs, before expanding.

'The Albatros course is really one of a kind because if you’re playing good golf, like any golf course really you can get round in a decent score. There are no

hidden agendas, no hidden traps, it’s a very true golf course if you’re hitting the ball well. However, if you’re not quite on your best day, it can gobble you up and chew you and completely ruin your golf swing. It can be a nightmare.’

Like many, Armitage is excited by the prospect of a Ryder Cup here. ‘It’s a fantastic finish, 15, 16, 17, 18. If matches go down the 18th and 17th it will be probably one of the best amphitheatres we’ve seen on both sides of the Atlantic to finish off a Ryder Cup. If that last point is played on the 18th on the Sunday night then it will be an amazing spectacle, it really will.’

Even the locals, he believes, for so long ambivalent about the event turning up on their doorstep, are finally taking notice. ‘I think people are really getting excited about it now. With 7.5m euros of preparation work going into the course, that got a lot of media attention here. Maybe it was just a wake-up to say that we’ve been talking about it for so many years but now actually something is happening.’

A little like soccer in America, the rise of golf in France is one of those perpetual sporting truisms often proposed with little hard evidence attached. Just how big is the French game?

FFgolf counts 408,000 ‘registered’ players at clubs and associations – which is to say, in a market of growing consumer flexibility, substantially more than 408,000 golfers. It estimates that 780,000 play the game regularly in some form or other, with two million playing occasionally and 6.5 million ‘interested’ in the sport.

KPMG’s latest report on golf participation in Europe actually makes France Europe’s fourth biggest golf market, behind England, Germany and Sweden. Encouragingly, the demographic profile of French players is happily divorced from the ghastly male skew of the British game, and means that the total number of female and junior ‘registered’ golfers in France is actually higher than in England.

Bien sûr, relative to other sports, it’s clear that golf is some way down the French pecking order. But it has grown rapidly. As recently as 1980, when Seve was winning the Masters for Spain, there were fewer than 40,000 registered players in l’Hexagone; an explosion of course-building between 1985 and 1995, which saw nearly 400 traditional-length tracks developed around the country, was matched with a boom in demand and by the turn of the century nearly 300,000 golfers were licensed to thrill on the spanking new infrastructure.Though the game is played to some extent all over France, it is possible to identify three broad geographic poles of interest. Some 160 years after Pau Golf Club became the first in mainland Europe, and 130 since Le Phare in Biarritz became the second, the rugby-mad southwest remains a key location. In the southeast, the Alps and Côte d’Azur – which hosts the only major played outside Britain and the US, the stylish Evian Championship, and has recently turned out former world No 15 Victor Dubuisson and the promising Romain Langasque – also has a sizeable concentration of players and courses. Finally, the greater Paris area combines history with strong facilities.

Paul Armitage, an Englishman who worked in the French game for a number of years before taking up his role at Le Golf National in 2014, is well qualified to judge the growth of the sport in his adopted homeland.

‘I think participation is definitely up,’ he told me. ‘People are turning to golf, not in a massive way, but it’s becoming more democratic, it’s becoming more cool, something to do, whereas maybe 15 or 20 years ago it still had that image of being reserved for `{`an`}` elite, of being so expensive. People are realising that you can play golf for one year for the price of going skiing for a week. There are some battles we are winning in the war against image.

France indeed provides a fascinating case study of how to boost participation in golf among non-traditional segments of the population. Back in 2009, faced with evidence that the French public found golf interesting but frequently inaccessible and unaffordable, it made the development of 100 ‘petites structures’ a central plank of its strategic ambition to land the Ryder Cup. Short, fun, well-kept, convenient facilities near urban centres, 10-15 euros a round, bring your mates, bring the family, bring the dog.‘A lot of our golf facilities in France were created by wealthy people, or farmers who had a bit of land,’ explained Armitage. ‘They weren’t necessarily created because there was a real need or a real business plan. A lot of them are miles out in the countryside, beautiful places in château parkland, but not adapted to the urban need for golf.'

The 100 new short courses, almost all now complete, make for interesting viewing. Nearly a third have synthetic greens and tees, enabling year-round play; though some are built on the grounds of existing clubs, others – such as a facility in St Etienne – are constructed on reclaimed industrial wasteland. Judging their success will take years, but anecdotal evidence suggests their tee shot has found the fairway: at a newly-opened six-hole course in the northern town of Amiens, for instance, the first grouping was three boys aged between seven and nine.

Armitage described a new nine-hole facility in Reims that is winning the battle to recruit new golfers. Accessible by tram from the town centre, offering a shop, restaurant, covered practice range and beginners’ coaching, and advertised by a man in shorts strumming his putter like an air guitar, this is not golf as we know it. ‘That is a pure Ryder Cup product. It is run by one of the chains and networks. The funding came from the local town council who had a piece of land. They created the most new golfers per capita last year.’

True enough, without a sharp spike in take-up it’s fair to expect les petites structures – and specifically their use of public handouts – to come under scrutiny. But this bold and diligently planned initiative surely deserves time to succeed. At the very least, striking pictures of beautifully landscaped, 18-hole pitch-and-putt courses, of families and children enjoying fun, cheap rounds of six-hole golf in the shadow of urban tower blocks, could not be further from the staid gin-and-tonic culture of the old British club game, and chapeau to that.One of the great challenges of developing golf in France – and one that seems to involve a paradoxical combination of chickens and eggs – is creating champions. FFgolf has certainly taken its share of flak for the country’s failure to penetrate the upper echelons of the global game; and when mega-talents like Thomas Pieters and Rahm are emerging from as close by as Belgium and northern Spain, the persistent absence of an elite Frenchman begins to look careless. But developing winners can be a haphazard business: just ask British tennis, whose lofty position atop the game owes pretty much everything to one single-minded family from Dunblane.

For French golf, the world rankings emit mixed messages, speaking of a certain strength in depth while hinting at a possible glass ceiling. This summer, one player was consistently ranked in the top 100 – Alexander Levy – while six were in or around the top 200; roll back 20 years and those figures were zero and two respectively, with Jean Van de Velde and Jean Louis Guepy ploughing a lonely furrow in the lower reaches.

Mention of Van de Velde – now heavily involved in the organisation of the French Open at Le Golf National – inevitably brings to mind the statistic that haunts French golf more than any other. Though the likes of Thomas Levet at Muirfield and Grégory Havret at Pebble Beach have also gone painfully close, Van de Velde’s aquatic adventures in the Barry Burn at Carnoustie preserved the unpalatable truth that Arnaud Massy’s win at Hoylake in 1907 was both the first and the last major victory by a Frenchman.

One player who briefly threatened to join the elite – and still might – is the mercurial Dubuisson. At his best, there is a grace, an artistry, a Latin flamboyance about the 27-year-old from Cannes, an elegance of touch that no Anglo-Saxon player could hope to replicate. This is a figure, it says, worth following around a golf course, a figure that kids would want to imitate. When he reaches into the bag, you sometimes expect him to pull out an épée and dance off down the fairway on his toes, swinging to and fro.

Alas, just as with Martin Kaymer in Germany and poor Matteo Manassero in Italy, the pressure of being the face of golf in a country where golf is superficially understood seems to have proved a draining, destabilising influence; you race for the light only to find it burns when you get there. But with two Turkish Open victories, two top-tens in majors and a highly successful Ryder Cup behind him, there is at least a strong body of work to fall back on.

We hope and expect that Victor Dubuisson will be back. And let us be equally confident that golf will continue to grow in his great country, France, for there cannot be, if you stop to think about it, any game better suited to the Gallic psyche. Those wondrous aesthetics, the showcasing of the beauty of the great outdoors; and that epic struggle, the melancholic pursuit of a perfection that dissolves without reason long before its essence truly can be appreciated. Forget love, faith and freedom: those great French philosophers could easily have been talking about golf.

Arnaud Massy won his fourth French Open aged 48 after an enforced career break for World War I, in which he was wounded during active service at Verdun. His victory in the British Open was the one that shaped his life; already resident in Scotland, he named his daughter Margot Hoylake. It was only in 2012, following the sterling efforts of historians Jean-Bernard Kazmierczak and Douglas Seaton, that his grave was discovered in Edinburgh’s neglected Newington cemetery.

Funds were raised for a new headstone, a ceremony was held and it was a fitting, if sadly overdue, way to close the story of his life – and the first remarkable chapter in the history of French golf.

The most fitting tribute of all, of course, would be for more flourishing chapters in that story to be written – and at Le Golf National this September, the quill will be firmly poised.