Green reading is a fascinating and yet sometimes frustrating concept to master, trying to visualise break and speed, the effects of grain, wind and the occasional spike mark – is it any wonder that at times putting becomes nothing more than a case of hit and hope? Learning to recognise the true line of a breaking putt is the first step to building up your confidence – and this impromptu beach lesson can help

Analysis by Dr Paul Hurrion

Learn to recognise the full visual

One of my keys to putting is to understand the difference between a good putt and a poor putt. You can misread a putt, pull it and hole the putt – does that make you a good putter? Hey, you got lucky… but two wrongs don’t always make a right. This style of putting would perhaps at best be streaky, but not one that will deliver a consistent, repeatable stroke.

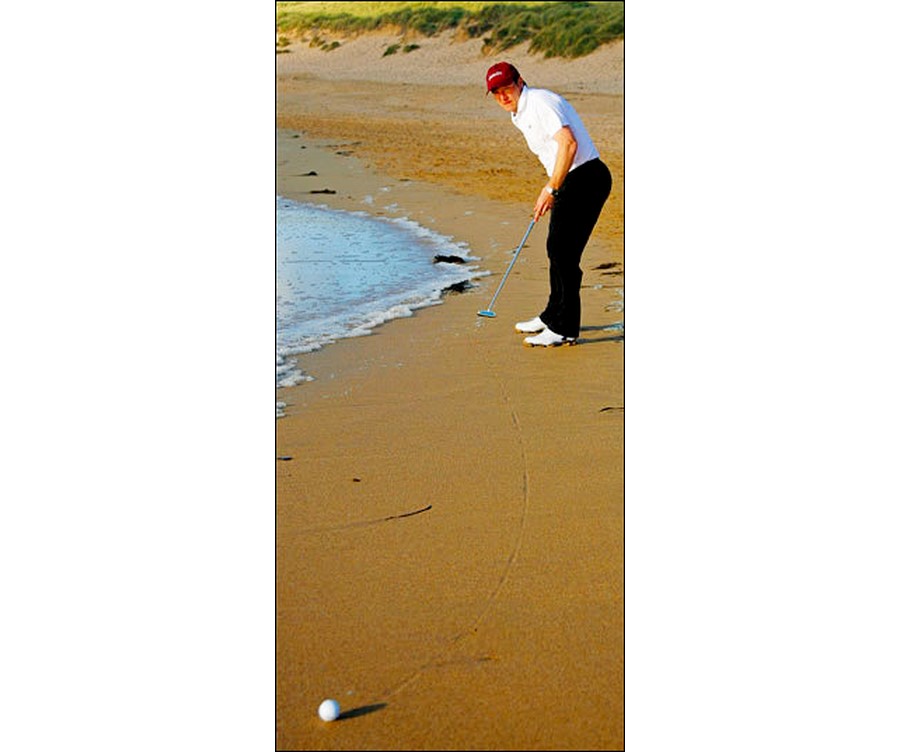

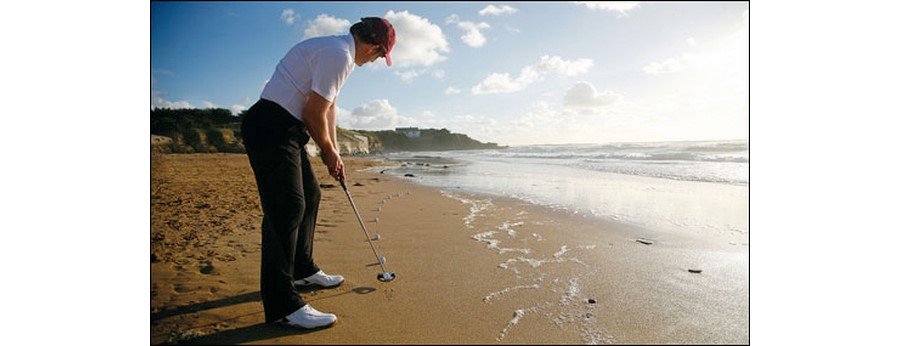

I find the majority of amateurs and even seasoned professionals tend to under read breaking putts, and through the course of this article I’m going to explain why. And how about this for a prop: using the golden sands of Constantine Bay here at Gi HQ in Cornwall, I’m going to provide a graphic illustration that will enhance your ability to visualise the true break Remember, gravity is a constant…

The first thing to understand is that gravity is constantly affecting the roll of the ball and how it breaks. In this inset image (below and repeated overleaf), the result of my first putt on the beach is clearly indicated, the path of the ball revealed by the track left in the sand. Upon closer inspection you can see the ball became slightly airborne after being struck and initially bounced several times on the sand before the frictional force between the sand and ball increases until true roll is achieved.

This combined state of sliding and rolling occurs before the ball ends up in a state of pure roll. Both Cochran and Stobbs [1] and Daish [2] indicate that a putted golf ball will be in a state of pure rolling (no skid) after travelling approximately 20% of the total length of the putt. However, recent research collected by my Quintic Consultancy [3] would suggest it is possible to achieve the state of pure roll within 10% of the total length of the putt.

Once true roll has been achieved, the ball will slow down at a consistent rate – remember gravity has a constant effect on the roll of the ball.

There’s always been lots of talk about how to best visualise the line of the putt across the green. Maybe the most popular notion is aiming the ball’s initial starting line (a projected straight line) adjacent to the hole; followed by aiming the putter to the apex of the putt. Regardless of technique, such visualising always stop at the hole!

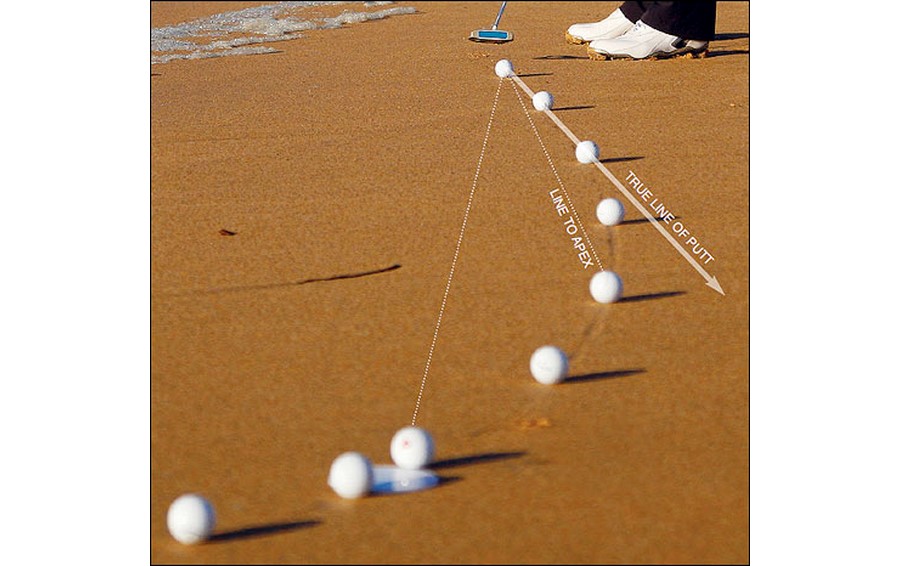

Those who believe in aiming at the apex of a putt are under-reading the borrow, as the graphics here reveal.

Almost all PGA Tour golfers I have worked with only focused at the hole (or certainly were drawn to the front of the hole), and didn’t focus on what I regard as the true path of the ball, extending some 18 inches or so beyond the hole.

Extension beyond the hole reveals the true line & entry

As you can see here in the photo , focusing on the path of the putt to the front of the hole doesn’t give you the true representation of the path and the shape of the putt over the duration of its journey.

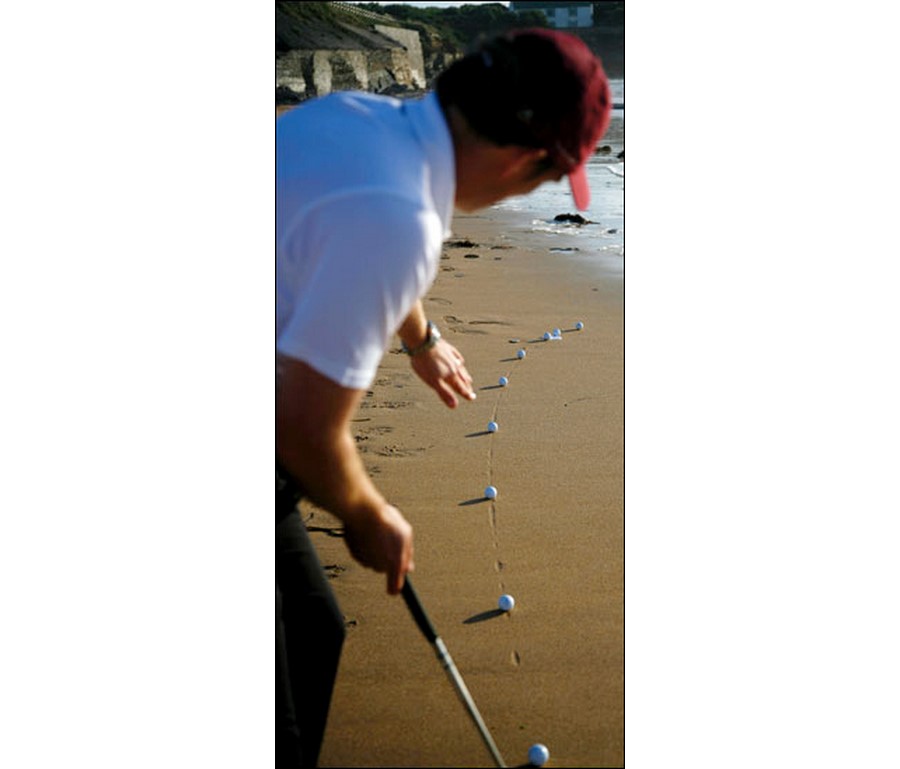

I have placed a white disk (to serve as our imaginary hole) 18” from where the ball finished, directly over the track the ball had taken. You can now clearly see the correct entry and exit point of the ball (the true middle of the hole from the perspective of the ball’s path) and also the position where the ball would have finished if the hole were covered in cellophane. This is the correct visual image, as this is the correct path of the ball (we know because the ball has taken this path!).

The key point to note here is how much the ball has broken once it has gone past the hole – remember gravity acts at a consistent rate… the visual of all the balls lined up on the correct path presents a powerful visual image!

So what is the correct starting line for this putt? The apex of the putt? NO! The apex of the putt is where the ball is the farthest away from the straight line that connects the ball and the hole. It is the point that is the highest point of a breaking putt. The only time you should ever aim at the apex is for a perfectly straight putt! For all breaking putts, you should always aim higher than the apex.

Look at the initial starting line the ball has taken for the putt in the sand (follow out the initial starting line) – notice how different it is to the ‘apex’ of the putt. How much would you have under read this particular putt? Finally, notice on the two identical images above, albeit with the power of ‘photoshop’, the effect of deleting the finish position of the ball and track behind the hole in the left-hand image.

Remember, they are the same image/stroke. With the finished position of the ball removed, just look at the visual image you are presented with! They look two completely different putts (both in terms of pace and starting line). Good luck if you are just stopping your visualisation at the hole… is that why you are under reading your putts.

Your new goal should be to imagine a tee peg 18” behind the hole. The position of the tee peg is crucial; you need to position the tee peg so that the only way the ball will come to rest by the tee peg (think of crown green bowls) is to run directly through the centre of the hole.

When putting across the slope of a green, your maximum variance in the horizontal launch angle (i.e. start line) for a successful putt is when the launch speed of the golf ball creates a path that sees the ball travel directly through the centre of the hole as it slows with enough pace to finish 18” beyond it. Just like the path the ball has made in the sand here.

So pack your putter along with your bucket and spade the next time you venture to the beach – and learn a valuable lesson that will make you a better putter on the course.

Refs: 1. A. Cochran and J. Stobbs. The Search for the Perfect Swing. Lippincott, New York. 1968.

2. C.B. Daish. The Physics of Ball Games. English Universities, London. 1972.

3. quintic.com – Quintic Consultancy Limited, Coventry, UK, 2012.