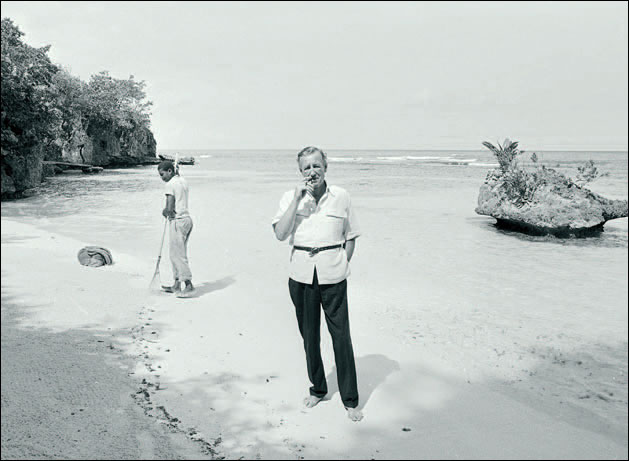

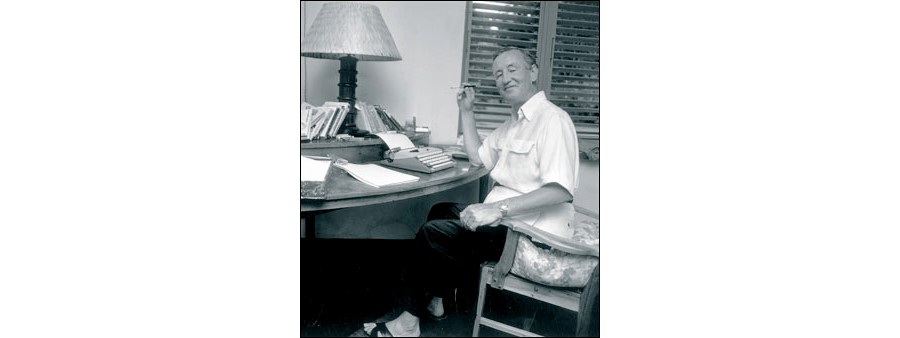

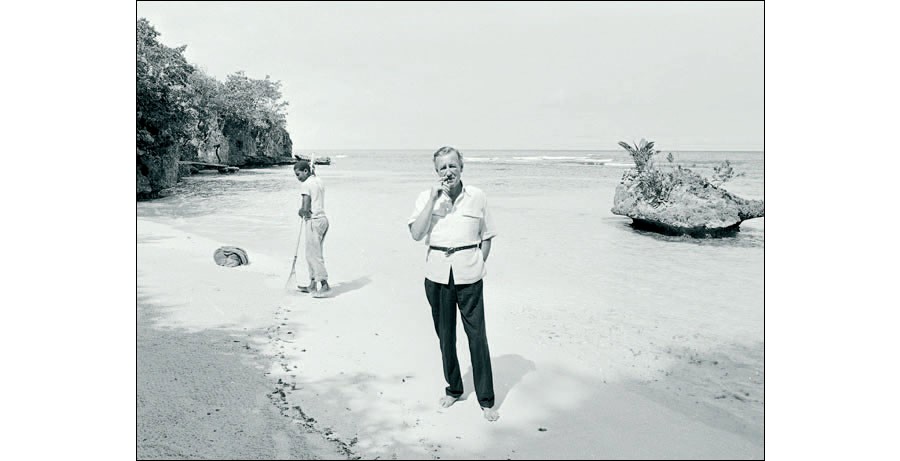

Without Ian Fleming there would have been no James Bond. In the spirit of the many retrospectives and events honoring the authors centenary, Dominic Pedler pays his respects to the man and his golf.

Ian Fleming’s golfing exploits go well beyond a few rounds at Royal St George’s to research the enthralling golf chapters in Goldfinger.

The creator of James Bond was an active member of the famous club at Sandwich from 1948 and was captain-elect in 1964, the year he died. By then St George’s had become a retreat for him with his returns to London usually limited to Tuesdays – “the only day when lunch was not served at the club”.

Fleming’s love affair with golf had begun almost half a century earlier, at Durnford preparatory school near Swanage in Dorset, which he attended prior to Eton. According to his biographer, Andrew Lycett, it was 1916 when the eight-year-old Fleming was encouraged to take his first tentative swings on a small plot seeded by the headmaster, Tom Pellatt. But his interest in the game took off in his mid-teens, when, following the death of his father, he spent long periods with his Granny Katie, who lived at Nettlebed, near Oxford – more importantly, near Huntercombe Golf Club.

No mean golfer herself, Katie would often drive her grandson in her Rolls-Royce to play 18 holes with him, with Lycett recording her eccentric habit of tipping the caddies with toothbrushes. The club history describes her as a “formidable lady member of 40 years”. Fleming kept up his interest in golf through his formative years and, while at university in Geneva, divided his time between skiing and golf, occasionally treating himself to a round at the plush Divonne club.

By his mid-20s, he had settled into a routine of playing golf with a close circle of friends at both St Georges and Huntercombe, helping his handicap (like James Bond’s) to dip to a respectable nine.

But a former Royal St George’s club pro and a playing partner of Fleming’s points out that this is misleading by modern standards. “In those days, handicaps at St George’s were calculated with reference to bogey. And, in Ian Fleming’s time, this was around the 78 mark,” says Cyril Whiting, now retired and living in his Sandwich home, who christened ‘The Maiden’ after the famous 6th hole. “Even when he came down to around seven at his lowest, that would have been equivalent to around 12 or 13 today.”

Whiting and his father, Albert, the St George’s club pro at the time of Goldfinger, both have the distinction of being immortalised in the book under the thinly-veiled pseudonyms of Alfred and Cecil Blacking.

Whiting confirms that much of the golfing trivia in the book have their basis in fact. Most notable is the pro shop small-talk in which Bond is told by Alfred that Cecil was “runner up in the Kent Championship last year”, and that he “should win it this year if he can only get out of the shop and on to the course a bit more”.

What a premonition. “I had been runner-up before, as the book says, but then I did go on to win it in 1959, a few months after Goldfinger was published,” remembers Whiting, who was a guest of honour at the recent Goldfinger Tournament arranged at the club by the Fleming family.

Fleming played regularly with these loyal pros, booking them as partners for his regular weekend foursomes with a small nucleus of golfing cronies. “My father or I would join up with him, depending on who was available,” says Cecil. “Even though the bets were never much more than a fiver, as I remember, there was always great pride at stake. He would play his heart out. He was very competitive and always like to get the edge”.

Not that Fleming was a purist. “He didn’t really have a swing,” says Whiting. “He had a flat, scything action, and he didn’t really bother with lessons – but then not many golfers did in those days. And I remember his incredibly strong grip, which would cause him to deloft the face at impact. It was impossible to club him.”

The caddie with the task of clubbing Fleming was the real-life Hawker, who caddies for Bond in Goldfinger. “Alf Hawkes was his name,” recounts Whiting. “He was the best caddie at the club, and was sought out by the best members and their sons when playing in top amateur competitions.”

Given his winter writing schedule at his Jamaican home, Goldeneye, Fleming was often absent from St George’s between Christmas and Easter, but would invariably return rejuvenated from his Caribbean jaunt. “One year I remember he arrived back at the club with this flash, left-hand drive American Thunderbird,” remembers Whiting. “And on the golf course, he’d tell us these great schemes, like smuggling banknotes in steel shafts or diamonds in the centre of golf balls. He was a character.”

Quite apart from his club regulars, Fleming played much golf with his close circle of highflying friends he dubbed ‘Le Cercle gastronomique et des jeux de hasard’. Bridge and draughts in the week would give way at weekends to car races down to the south coast for golf at favourite haunts such as Cooden Beach, Rye and over to Le Touquet and Deauville. Fleming enjoyed a particularly hedonistic golfing jolly at the recently opened Gleneagles resort in June 1934. He and 50 friends (including what he described as “assorted wives and concubines”) travelled from London on a private train, with one carriage for gambling and another for dancing. A photograph shows him striding the fairway of the King’s Course with the MP for Bath, Charlie Baillie Hamilton. The cost of the whole weekend was ten guineas.

Hole #1 on the Jack Nicklaus-designed Centenary Course, host of the Ryder Cup in 2014

Even during some of his own tricky overseas assignments, Fleming would find an excuse to play golf. While in Tangier in 1957, for undercover research into diamond smuggling with former MI5 agent John Collard, Fleming insisted they have a game at the Diplomatic Country Club. Despite both playing off nine, Ian failed to win a hole, being “too often in the rough ablaze with irises and asphodel, which line the dry waterhouses around and over which the course has been constructed”, he is quoted in Lycett’s biography.

Fleming kept up with his Old Etonian golfing friends, playing occasionally in the public school Halford Hewitt tournament at Deal, and later gave the OEGS a large chamber pot he christened ‘The James Bond All Purpose Grand Challenge Trophy Vase’, which many members considered in poor taste. He continued to play with various Old Etonians in later life when rediscovering the joys of Huntercombe with Sir Jock Campbell, who lived near the course at Nettlebed.

It was during an Old Etonian golfing weekend at Rye that Fleming was taken ill with heart palpitations, a condition that would plague him thereafter. Not long after, he took his wife, Ann, to Venice for a quiet holiday. But to her dismay they bumped into Count Paul Munster, an old White’s Club golfing partner of Fleming’s from the 1930s, who duly insisted they spend the week playing at the Golf du Lido. Fleming jumped at the chance to sample the same “browning, undulating fairways” that James Bond himself would briefly encounter in Risico, one of the short stories published in For Your Eyes Only.

Meanwhile, father-and-son Whiting were not the only real-life golfing characters to find themselves immortalised in James Bond stories. Hilary Bray (007’s alter ego from the Royal College of Arms in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service) was another Kent based friend who often made up a foursome with Fleming at bridge as well as golf. Indeed, he proposed Fleming’s membership at Royal St George’s in 1948. Then there was Fleming’s regular golf partner, scratch St George’s member, John Blackwell, whose stories of lie-improving in the Maiden bunker by unscrupulous opponents inspired the similar incident in Goldfinger.

Blackwell himself gets a mention by name in that book, briefly surfacing as a “pleasant spoken Import and Export merchant”, although he apparently was none too pleased that his character was linked with the heroin trade in Central America. Meanwhile, Blackwell should get extra credit for inspiring the name of the eponymous villain himself, telling Fleming about the famous modern architect of the day, Erno Goldfinger, who was married to one of his cousins. Sometimes the golf connections in the Bond stories were even more subtle. Who, for example, would ever have guessed the origins of the opening line of Thunderball had it not been for a lengthy plagiarism lawsuit during which Fleming was challenged to provide details about the source of his material for the plot?

“It was one of those days when it seemed to James Bond that all life, as someone put it, was nothing but a heap of six to four against,” it reads. That someone was another of Fleming’s golf partners, the fine amateur, John Beck, who captained the GB&I Walker Cup team to their historic 1938 victory at St Andrews.

One way or another, golf played an important part in the life of Ian Fleming. On August 11, 1964, he had his last lunch in the clubhouse of his beloved Royal St George’s. In the early hours of the following morning, he passed away at the Kent & Canterbury hospital. Lived, and let die.

Fleming & the chamber pot trophy

Having enjoyed the company of many Old Etonians out on the links, Fleming christened this rather ornate chamber pot ‘The James Bond All Purpose Grand Challenge Trophy Vase’, which he donated to the Old Etonians Golf Society in 1962.

The OEGS have competed annually for the trophy, usually at Royal St George’s, apart from a few years when it was stolen from an open-top sports car before mysteriously turning up on a TV quiz programme on unusual objects.

Huntercombe… A perfect English club

From behind the wheel of an Aston Martin – DB5, in silver, naturally – the golf club at Huntercombe lies approximately 40 minutes southwest of London, in the leafy Oxfordshire countryside, not far from Henley-on-Thames.

This private members’ club is remarkable for the fact that it is not remarkable at all. It is a quintessentially English institution – one which James Bond volunteered to Auric Goldfinger as his home club when quizzed on the matter of his handicap before their epic encounter at Royal St Mark’s (the pseudonym given to Royal St George’s in the book.)

“I was playing with the professional. I will play with you instead.” Goldfinger was stating a fact. There was no doubt that Goldfinger was hooked. Now Bond must play hard to get. “Why not some other time? I’ve come to order a club. Anyway, I’m not in practice. There probably isn’t a caddie.” Bond was being as rude as he could. Obviously the last thing he wanted to do was play with Goldfinger.

“I also haven’t played for some time.” (Bloody liar, thought Bond.) “Ordering a club will not take a moment.” Goldfinger turned back into the shop. “Blacking, have you got a caddie for Mr Bond?”

“Yes, sir?”

“Then it is arranged.”

Bond wearily thrust his driver back into his bag. “Well, all right then.” He thought of a final way of putting Goldfinger off. He said roughly,”But I warn you I like playing for money. I can’t be bothered to knock a ball round just for the fun of it.” Bond felt pleased with the character he was building for himself.

Was there a glint of triumph, quickly concealed, in Goldfinger’s pale eyes? He said indifferently, “That suits me. Anything you like. Off handicap, of course. I think you said you’re nine.” “Yes.”

Goldfinger said carefully,”Where, may I ask?” “Huntercombe.” Bond was also nine at Sunningdale. Huntercombe was an easier course. Nine at Huntercombe wouldn’t frighten Goldfinger.

“And I also am nine. Here. Up on the board. So it’s a level game. Right?”

With $10,000 dollars at stake (the sum being the amount Bond had charged a Mr Du Pont to prove Goldfinger’s cheating at cards some weeks earlier in Miami), Huntercombe was the perfect, comparatively anonymous, English club for Bond’s purposes.

And so it remains to this day, for anyone. It gets a mention in the novel because Bond’s creator, Ian Fleming, was a member there from 1932 until his untimely death in 1964. He was also a pretty useful nine, according to members who knew and remember him.

As for the course itself, Huntercombe was originally founded at the turn of the century by Willie Park, one of the great professionals of his day, whose father (Willie Park Senior) won the first ever Open in 1860 – and won it again in 1863, 1866 and 1875.YoungWillie himself won the championship in 1887 and 1889, and was widely known for a long-standing challenge to play anyone in the world for £100. In 1889, he was engaged to design and supervise construction of the Old Course at Sunningdale, Bond’s other club.

Like most courses which are noticebly short on the card, the difficulties at Huntercombe are chiefly concentrated on and around the greens. Many feature huge contours and two-tier plateaus, so there is plenty of opportunity to rack up a score with the putter.Over the years, many of the original bunkers have been allowed to grow over for ease of maintenance, and the course is littered with grass ‘pots’ and hollows, in many cases more dangerous than sand. Early posters advertised the course as an example of a ‘links golf inland’, and striking the ball off the trim turf remains one of Huntercombe’s distinct pleasures.

Reproduced with kind permission of Golf International.